what are the components of milk that people are allergic to

| Milk allergy | |

|---|---|

| |

| A glass of cow'south milk | |

| Specialty | Allergology |

| Frequency | 0.6%[ane] |

Milk allergy is an agin immune reaction to one or more than proteins in cow's milk. When allergy symptoms occur, they can occur speedily or have a gradual onset. The former may include anaphylaxis, a potentially life-threatening condition which requires treatment with epinephrine among other measures. The latter tin take hours to days to announced, with symptoms including atopic dermatitis, inflammation of the esophagus, enteropathy involving the small intestine and proctocolitis involving the rectum and colon.[2]

In the United States, xc% of allergic responses to foods are caused by 8 foods, with cow's milk being the most mutual.[3] Recognition that a modest number of foods are responsible for the majority of nutrient allergies has led to requirements to prominently list these common allergens, including dairy, on nutrient labels.[4] [five] [6] [7] One role of the immune system is to defend against infections by recognizing foreign proteins, but it should not over-react to nutrient proteins. Heating milk proteins can cause them to become denatured, pregnant to lose their iii-dimensional configuration, and thus lose allergenicity; for this reason dairy-containing baked goods may exist tolerated while fresh milk triggers an allergic reaction.

Management is by avoiding eating any dairy foods or foods that contain dairy ingredients.[8] In people with rapid reactions (IgE-mediated milk allergy), the dose capable of provoking an allergic response can exist as low every bit a few milligrams, so recommendations are to avoid dairy strictly.[ix] [10] The declaration of the presence of trace amounts of milk or dairy in foods is non mandatory in any country, with the exception of Brazil.[5] [11] [12]

Milk allergy affects between 2% and 3% of babies and young children.[eight] [13] To reduce hazard, recommendations are that babies should be exclusively breastfed for at least four months, preferably 6 months, before introducing moo-cow's milk. If in that location is a family unit history of dairy allergy, then soy infant formula can be considered, just about 10 to fifteen% of babies allergic to cow'south milk volition also react to soy.[fourteen] The majority of children outgrow milk allergy, but for most 0.4% the status persists into adulthood.[xv] Oral immunotherapy is being researched, but it is of unclear benefit.[xvi] [17]

Signs and symptoms [edit]

Rapid and delayed response [edit]

Nutrient allergies tin have rapid-onset (from minutes up to 2 hours), delayed-onset (up to 48 hours or even 1 calendar week), or combinations of both, depending on the mechanisms involved. The difference depends on the types of white blood cells involved. B cells, a subset of white claret cells, rapidly synthesize and secrete immunoglobulin E (IgE), a class of antibody which bind to antigens, i.east., the foreign proteins. Thus, firsthand reactions are described as IgE-mediated. The delayed reactions involve non-IgE-mediated immune mechanisms initiated past B cells, T cells, and other white blood cells. Unlike with IgE reactions, there are no specific biomarker molecules circulating in the claret, and then, confirmation is by removing the suspect food from the diet and encounter if the symptoms resolve.[xviii]

Symptoms [edit]

IgE-mediated symptoms include: rash, hives, itching of the mouth, lips, tongue, throat, eyes, peel, or other areas, swelling of the lips, tongue, eyelids, or the whole face, difficulty swallowing, runny or congested olfactory organ, hoarse voice, wheezing, shortness of jiff, diarrhea, abdominal pain, lightheadedness, fainting, nausea and vomiting.[ description needed ] Symptoms of allergies vary from person to person and may too vary from incident to incident.[19] Serious danger regarding allergies can begin when the respiratory tract or blood circulation is affected. The quondam can exist indicated by wheezing, a blocked airway and cyanosis, the latter past weak pulse, pale skin, and fainting. When these symptoms occur, the allergic reaction is called anaphylaxis.[19] Anaphylaxis occurs when IgE antibodies are involved, and areas of the body that are not in straight contact with the food go afflicted and show astringent symptoms.[xix] [20] Untreated, this tin proceed to vasodilation, a low blood pressure situation chosen anaphylactic daze, and very rarely, death.[6] [20]

Not lgE mediated symptoms [edit]

For milk allergy, non-IgE-mediated responses are more common than IgE-mediated.[21] The presence of sure symptoms, such as angioedema or atopic eczema, is more likely related to IgE-mediated allergies, whereas non-IgE-mediated reactions manifest equally gastrointestinal symptoms, without skin or respiratory symptoms.[18] [22] Within non-IgE cow'south milk allergy, clinicians distinguish among food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome (FPIES), food poly peptide-induced allergic proctocolitis (FPIAP) and nutrient protein-induced enteropathy (FPE). Common trigger foods for all are cow's milk and soy foods (including soy babe formula).[22] [23] FPIAP is considered to exist at the milder end of the spectrum and is characterized by intermittent bloody stools. FPE is identified by chronic diarrhea which volition resolve when the offending food is removed from the babe's nutrition. FPIES can be severe, characterized by persistent airsickness, 1 to iv hours after an allergen-containing food is ingested, to the point of sluggishness. Watery and sometimes encarmine diarrhea can develop 5 to x hours later the triggering meal, to the point of aridity and low blood pressure level. Infants reacting to cow's milk may besides react to soy formula, and vice versa.[23] [24] International consensus guidelines have been established for the diagnosis and treatment of FPIES.[24]

Mechanisms [edit]

Weather caused by food allergies are classified into three groups according to the mechanism of the allergic response:[25]

- IgE-mediated (classic) – the most common type, manifesting every bit acute changes that occur soon after eating, and may progress to anaphylaxis

- Not-IgE mediated – characterized by an immune response not involving IgE; may occur hours to days afterward eating, complicating the diagnosis

- IgE- and not-IgE-mediated – a hybrid of the to a higher place ii types

Allergic reactions are hyperactive responses of the immune organization to by and large innocuous substances, such as proteins in the foods we eat. Some proteins trigger allergic reactions while others do not. One theory is resistance to digestion, the thinking existence that when largely intact proteins reach the small intestine the white claret cells involved in immune reactions volition be activated.[26] The heat of cooking structurally degrades poly peptide molecules, potentially making them less allergenic.[27] Allergic responses tin be divided into two phases: an acute response that occurs immediately after exposure to an allergen, which can and so either subside or progress into a "late-phase reaction," prolonging the symptoms of a response and resulting in more tissue harm.[28] [29]

In the early on stages of acute allergic reaction, lymphocytes previously sensitized to a specific protein or protein fraction react by quickly producing a particular type of antibiotic known as secreted IgE (sIgE), which circulates in the blood and binds to IgE-specific receptors on the surface of other kinds of allowed cells called mast cells and basophils. Both of these are involved in the astute inflammatory response.[28] Activated mast cells and basophils undergo a process chosen degranulation, during which they release histamine and other inflammatory chemical mediators (cytokines, interleukins, leukotrienes, and prostaglandins) into the surrounding tissue causing several systemic effects, such equally vasodilation, mucous secretion, nerve stimulation, and smooth muscle contraction. This results in runny nose, itchiness, shortness of breath, and potentially anaphylaxis. Depending on the individual, the allergen, and the fashion of introduction, the symptoms can exist system-wide (classical anaphylaxis), or localized to particular torso systems; asthma is localized to the respiratory organization, while eczema is localized to the peel.[28]

After the chemic mediators of the acute response subside, late-stage responses can often occur due to the migration of other white blood cells such equally neutrophils, lymphocytes, eosinophils, and macrophages to the initial reaction sites. This is unremarkably seen 2–24 hours after the original reaction.[29] Cytokines from mast cells may likewise play a role in the persistence of long-term effects. Late-phase responses seen in asthma are slightly different from those seen in other allergic responses, although they are still caused by release of mediators from eosinophils.[xxx]

Vi major allergenic proteins from cow's milk have been identified: αs1-, αs2-, β-, and κ-casein from casein proteins and α-lactalbumin and β-lactoglobulin from whey proteins. There is some cross-reactivity with soy protein, peculiarly in non-IgE mediated allergy. Heat tin reduce allergenic potential, so dairy ingredients in baked goods may be less likely to trigger a reaction than milk or cheese.[ citation needed ] For milk allergy, non-IgE-mediated responses are more common than IgE-mediated. The onetime tin can manifest as atopic dermatitis and gastrointestinal symptoms, peculiarly in infants and immature children. Some will display both, and then that a child could react to an oral nutrient claiming with respiratory symptoms and hives (skin rash), followed a twenty-four hours or two later with a flare upward of atopic dermatitis and gastrointestinal symptoms, including chronic diarrhea, blood in the stools, gastroesophageal reflux illness (GERD), constipation, chronic vomiting and colic.[2]

Diagnosis [edit]

Peel prick testing for allergies. For a positive response, the skin will become red and raised.

Diagnosis of milk allergy is based on the person's history of allergic reactions, skin prick exam (SPT), patch test, and measurement of milk protein specific serum IgE. A negative IgE examination does non rule out not-IgE-mediated allergy, also described as cell-mediated allergy. Confirmation is past double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenges, conducted past an allergy specialist. SPT and IgE have a sensitivity of effectually 88% merely specificity of 68% and 48%, respectively, meaning these tests volition probably find a milk sensitivity but may also be faux-positive for other allergens.[31]

Attempts accept been made to place SPT and IgE responses accurate enough to avoid the demand for confirmation with an oral food claiming. A systematic review stated that in children younger than 2 years, cutting-offs for specific IgE or SPT seem to exist more homogeneous and may be proposed. For older children, the tests were less consequent. It ended "None of the cutting-offs proposed in the literature can exist used to definitely ostend cow's milk allergy diagnosis, either to fresh pasteurized or to baked milk."[32]

Differential diagnosis [edit]

The symptoms of milk allergy tin can exist confused with other disorders that nowadays similar clinical features, such as lactose intolerance, infectious gastroenteritis, celiac disease, not-celiac gluten sensitivity, inflammatory bowel disease, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, and pancreatic insufficiency, among others.[33] [34] [35]

Lactose intolerance [edit]

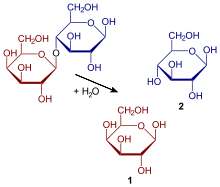

Hydrolysis of the disaccharide lactose to glucose and galactose

Milk allergy is singled-out from lactose intolerance, which is a nonallergic nutrient sensitivity caused by the lack of the enzyme lactase in the small intestines to suspension lactose downwardly into glucose and galactose. The unabsorbed lactose reaches the big intestine, where resident bacteria use it for fuel, releasing hydrogen, carbon dioxide and methane gases. These gases are the cause of abdominal hurting and other symptoms.[33] [36] Lactose intolerance does not cause damage to the gastrointestinal tract.[37] In that location are four types: primary, secondary, developmental and built.[38] Primary lactose intolerance is caused past decreasing levels of lactase brought on past age.[38] Secondary lactose intolerance results from injury to the small intestine, such as from infection, celiac affliction, inflammatory bowel illness or other diseases.[38] [39] Developmental lactose intolerance may occur in premature babies and usually improves over a short period of time.[38] Congenital lactose intolerance is an extremely rare genetic disorder in which little or no lactase is made from birth.[38]

Prevention [edit]

Research on prevention addresses the question of whether it is possible to reduce the risk of developing an allergy in the first place. Reviews concluded that at that place is no strong evidence to recommend changes to the diets of pregnant or nursing women as a ways of preventing the development of food allergy in their infants.[40] [41] [42] For mothers of infants considered at high adventure of developing moo-cow's milk allergy because of a family unit history, at that place is some evidence that the nursing female parent avoiding allergens may reduce risk of the child developing eczema, but a Cochrane review concluded that more inquiry is needed.[41]

Guidelines from various regime and international organizations recommend that for the lowest allergy chance, infants be exclusively breastfed for 4–6 months. At that place does not announced to be whatsoever do good to extending that flow across six months.[42] [43] If a nursing mother decides to start feeding with an infant formula prior to 4 months the recommendation is to use a formula containing cow's milk proteins.[44]

A dissimilar consideration occurs when at that place is a family history – either parents or older siblings – of milk allergy. The three options to avoiding formula with intact cow'south milk proteins are substituting a production containing either extensively hydrolyzed milk proteins, or a non-dairy formula, or one utilizing free amino acids. The hydrolyzation procedure breaks intact proteins into fragments, in theory reducing allergenic potential. In 2016, the U.S. Food and Drug Assistants (FDA) approved a label claim for hydrolyzed whey protein being hypoallergenic.[45] However, a meta-assay published the same year disputed this merits, concluding that, based on dozens of clinical trials, there was insufficient bear witness to back up a claim that a partially hydrolyzed formula could reduce the risk of eczema.[46] Soy formula is a common substitution, but infants with milk allergy may likewise have an allergic response to soy formula.[47] Hydrolyzed rice formula is an selection, as are the more than expensive amino acid-based formulas.[44]

Treatment [edit]

The need for a dairy-gratuitous diet should be reevaluated every six months by testing milk-containing products low on the "milk ladder", such as fully cooked, i.e., baked foods, containing milk, in which the milk proteins have been denatured, and ending with fresh cheese and milk.[8] [48] Desensitization via oral immunotherapy is considered experimental.[49]

Treatment for accidental ingestion of milk products by allergic individuals varies depending on the sensitivity of the person. An antihistamine, such as diphenhydramine (Benadryl), may be prescribed. Sometimes prednisone will be prescribed to forbid a possible late-stage type I hypersensitivity reaction.[50] Severe allergic reactions (anaphylaxis) may crave treatment with an epinephrine pen, i.eastward., an injection device designed to be used past a non-healthcare professional when emergency treatment is warranted. A second dose is needed in 16–35% of episodes.[51]

Avoiding dairy [edit]

Virtually people discover it necessary to strictly avoid whatever item containing dairy ingredients.[ix] The reason is that the private threshold dose capable of provoking an allergic reaction can exist quite small, specially in infants. An estimated 5% react to less than 30 milligrams of dairy proteins, and 1% react to less than 1 milligram.[52] A more recent review calculated that the eliciting threshold dose for an allergic reaction in 1% of people (ED01) with confirmed cow'due south milk allergy is 0.ane mg of cow'south milk poly peptide.[53]

Across the obvious (anything with milk, cheese, cream, curd, butter, ghee or yogurt in the name), in countries where allergen labeling is mandatory, the ingredient list is supposed to listing all ingredients. Anyone with or caring for a person with a dairy protein allergy should ever carefully read food package labels, every bit sometimes even a familiar brand undergoes an ingredient alter.[54] In the U.Southward., for all foods except meat, poultry and egg processed products and most alcoholic beverages, if an ingredient is derived from 1 of the required-characterization allergens, then it must either have the food proper name in parentheses, for instance "Casein (milk)," or every bit an alternative, in that location must be a argument separate just adjacent to the ingredients listing: "Contains milk" (and whatever other of the allergens with mandatory labeling).[5] [54] [55] [56] Dairy-sourced protein ingredients include casein, caseinates, whey and lactalbumin, among others.[54] [57] The U.S. FDA has a recall process for foods that incorporate undeclared allergenic ingredients.[58] The Academy of Wisconsin has a list of foods that may contain dairy proteins, yet are not always obvious from the proper noun or type of nutrient.[57] This list contains the following examples:

- Bread, baked appurtenances and desserts

- Caramel and nougat candies

- Cereals, crackers, food bars

- Chewing gum

- Chocolate ('milk' and 'nighttime')

- "Cream of..." soups

- Creamy pasta sauces

- Flossy salad dressings

- Eggnog

- Flavored white potato chips

- Hot dogs and lunch meat

- Instant mashed potatoes

- Margarine

- Medical food beverages

- Non-dairy creamer

- Sherbet

- Pudding and custard

There is a distinction between "Contains ___" and "May contain ___." The first is a deliberate improver to the ingredients of a food, and is required. The second addresses unintentional possible inclusion of ingredients, in this instance dairy-sourced, during transportation, storage or at the manufacturing site, and is voluntary, and is referred to equally precautionary allergen labeling (PAL).[five] [54] [11]

Milk from other mammalian species (goat, sheep, etc.) should not be used every bit a substitute for cow'south milk, as milk proteins from other mammals are oft cross-reactive.[59] Nevertheless, some people with cow's milk allergy tin can tolerate goat's or sheep's milk, and vice versa. Milk from camels, pigs, reindeer, horses, and donkeys may too exist tolerated in some cases.[47] Probiotic products have been tested, and some constitute to contain milk proteins which were not e'er indicated on the labels.[threescore] [61]

Cross-reactivity with soy [edit]

Infants – either notwithstanding 100% breastfeeding or on babe formula – and too young children may be prone to a combined cow'due south milk and soy poly peptide allergy, referred to as "milk soy poly peptide intolerance" (MSPI). A U.S. country regime website presents the concept, including a recommendation that nursing mothers discontinue eating any foods that contain dairy or soy ingredients.[62] In opposition to this recommendation, a published scientific review stated that there was not yet sufficient evidence in the human trial literature to conclude that maternal dietary food avoidance during lactation would forbid or treat allergic symptoms in breastfed infants.[41]

A review presented information on milk allergy, soy allergy and cross-reactivity between the ii. Milk allergy was described as occurring in 2.ii% to two.viii% of infants and declining with age. Soy allergy was described as occurring in cypher to 0.7% of young children. According to several studies cited in the review, between x% and 14% of infants and young children with confirmed moo-cow'due south milk allergy were adamant to also exist sensitized to soy and in some instances have a clinical reaction subsequently consuming a soy-containing food. The research did non accost whether the cause was two separate allergies or a cross-reaction due to a similarity in protein structure, as which occurs for cow's milk and goat'south milk.[47] Recommendations are that infants diagnosed as allergic to cow's milk infant formula be switched to an extensively hydrolyzed protein formula rather than a soy whole poly peptide formula.[47] [63]

Prognosis [edit]

Milk allergy typically presents in the starting time year of life. The majority of children outgrow milk allergy by the age of 10 years.[8] [xiii] One large clinical trial reported resolutions of 19% by age 4 years, 42% by age 8 years, 64% by age 12 years, and 79% past 16 years.[64] Children are often better able to tolerate milk equally an ingredient in baked goods relative to liquid milk. Childhood predictors for adult-persistence are anaphylaxis, high milk-specific serum IgE, robust response to the skin prick test and absence of tolerance to milk-containing baked foods.[13] Resolution was more probable if baseline serum IgE was lower,[64] or if IgE-mediated allergy was absent-minded so that all that was present was cell-mediated, non-IgE allergy.[8] People with confirmed cow's milk allergy may likewise demonstrate an allergic response to beef, more so to rare beefiness versus well-cooked beef. The offending protein appears to exist bovine serum albumin.[65]

Milk allergy has consequences. In a U.Due south. government nutrition and health surveys conducted in 2007–2010, half-dozen,189 children ages ii–17 years were assessed. For those classified as moo-cow's milk allergic at the fourth dimension of the survey, mean weight, height, and trunk-mass index were significantly lower than their non-allergic peers. This was non true for children with other food allergies. Nutrition assessment showed a pregnant 23% reduction of calcium intake and near-significant trends for lower vitamin D and total calorie intake.[66]

Epidemiology [edit]

Incidence and prevalence are terms commonly used in describing disease epidemiology. Incidence is newly diagnosed cases, which tin can exist expressed every bit new cases per year per million people. Prevalence is the number of cases alive, expressible every bit existing cases per meg people during a period of time.[67] The pct of babies in developed countries with milk allergy is betwixt two% and iii%. This gauge is for antibiotic-based allergy; figures for allergy based on cellular immunity are unknown.[8] The percentage declines every bit children get older. National survey data in the U.S. nerveless from 2005–2006 showed that from historic period six and older, the percentage with IgE-confirmed milk allergy was under 0.4%.[fifteen] For all age groups, a review conducted in Europe estimated 0.6% had milk allergy.[one]

Club and culture [edit]

Dairy allergy was one of the primeval food allergies to be recorded. An ancient Greek medical text attributed to the doctor Hippocrates (c. 460 – c. 370 BC) notes in the context of a description of how some foods are harmful to sure individuals merely not others, "...cheese does not harm all men akin; some can consume their make full of it without the slightest injure, nay, those it agrees with are wonderfully strengthened thereby. Others come off badly." The text attempts to explicate the reaction to the cheese in terms of Hippocratic humorism, stating that some constitutions are naturally "hostile to cheese, and [are] roused and stirred to action under its influence."[68]

With the passage of mandatory labeling laws, food allergy awareness has definitely increased, with impacts on the quality of life for children, their parents and their firsthand caregivers.[69] [70] [71] [72] In the U.Southward., the Food Allergen Labeling and Consumer Protection Act of 2004 (FALPA) causes people to be reminded of allergy problems every time they handle a food bundle, and restaurants take added allergen warnings to menus. School systems have protocols nigh what foods tin can be brought into the school. Despite all these precautions, people with serious allergies are aware that adventitious exposure can hands occur at other peoples' houses, at school or in restaurants.[73] Food fear has a meaning touch on on quality of life.[71] [72] Finally, for children with allergies, their quality of life is besides affected past deportment of their peers. At that place is an increased occurrence of bullying, which can include threats or acts of deliberately being touched with foods they need to avoid, also having their allergen-gratis food deliberately contaminated.[74]

Regulation of labeling [edit]

An case of "MAY CONTAIN TRACES OF..." as a means of listing trace amounts of allergens in a food product due to cross-contamination during manufacture.

In response to the adventure that certain foods pose to those with food allergies, some countries have responded by instituting labeling laws that require food products to clearly inform consumers if their products contain major allergens or byproducts of major allergens among the ingredients intentionally added to foods. Nevertheless, there are no labeling laws to mandatory declare the presence of trace amounts in the final production equally a consequence of cross-contagion, except in Brazil.[4] [v] [7] [xi] [54] [55] [56] [12]

Ingredients intentionally added [edit]

In the The states, FALCPA requires companies to disclose on the label whether a packaged food production contains a major food allergen added intentionally: cow's milk, peanuts, eggs, shellfish, fish, tree nuts, soy and wheat.[4] This list originated in 1999 from the Globe Health System Codex Alimentarius Commission.[11] To meet FALCPA labeling requirements, if an ingredient is derived from one of the required-label allergens, and so it must either accept its "nutrient sourced proper noun" in parentheses, for instance "Casein (milk)," or every bit an culling, at that place must be a argument split up only side by side to the ingredients list: "Contains milk" (and any other of the allergens with mandatory labeling).[4] [54] Dairy food listing is as well mandatory in the European Marriage and more than a dozen other countries.[7] [eleven]

FALCPA applies to packaged foods regulated by the FDA, which does not include poultry, most meats, sure egg products, and most alcoholic beverages.[5] Withal, some meat, poultry, and egg processed products may incorporate allergenic ingredients, such equally added milk proteins. These products are regulated by the Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS), which requires that whatsoever ingredient be alleged in the labeling only past its common or usual proper name. Neither the identification of the source of a specific ingredient in a parenthetical statement nor the apply of statements to alert for the presence of specific ingredients, like "Contains: milk", are mandatory according to FSIS.[55] [56]

In the U.South., at that place is no federal mandate to accost the presence of allergens in drug products. FALCPA does non apply to medicines nor to cosmetics.[75] FALCPA also does non apply to nutrient prepared in restaurants.[76] [4]

Trace amounts equally a effect of cross-contamination [edit]

The value of allergen labeling other than for intentional ingredients is controversial. This concerns labeling for ingredients present unintentionally equally a consequence of cantankerous-contact or cantankerous-contamination at any point along the nutrient chain (during raw material transportation, storage or handling, due to shared equipment for processing and packaging, etc.).[five] [11] Experts in this field propose that if allergen labeling is to be useful to consumers, and healthcare professionals who suggest and treat those consumers, ideally there should be agreement on which foods require labeling, threshold quantities below which labeling may be of no purpose, and validation of allergen detection methods to test and potentially remember foods that were deliberately or inadvertently contaminated.[77] [78]

Labeling regulations take been modified to provide for mandatory labeling of ingredients plus voluntary labeling, termed precautionary allergen labeling (PAL), also known equally "may contain" statements, for possible, inadvertent, trace amount, cross-contamination during product.[xi] [79] PAL labeling can be disruptive to consumers, especially as there can be many variations on the wording of the warning.[79] [lxxx] As of 2014[update], PAL is regulated only in Switzerland, Japan, Argentina, and South Africa. Argentine republic decided to prohibit precautionary allergen labeling since 2010, and instead puts the onus on the manufacturer to control the manufacturing process and characterization only those allergenic ingredients known to be in the products. South Africa does not permit the apply of PAL, except when manufacturers demonstrate the potential presence of allergen due to cantankerous-contagion through a documented adventure assessment despite adherence to Good Manufacturing Do.[xi] In Australia and New Zealand, there is a recommendation that PAL be replaced by guidance from VITAL 2.0 (Vital Incidental Trace Allergen Labelling). A review identified "the eliciting dose for an allergic reaction in 1% of the population" as 0.01 mg for cow'south milk. This threshold reference dose (and similar results for egg, peanut and other proteins) volition provide nutrient manufacturers with guidance for developing precautionary labelling and give consumers a better idea of what might be accidentally in a food product beyond "may comprise."[53] [81] VITAL 2.0 was developed by the Allergen Bureau, a nutrient industry-sponsored, not-authorities system.[82] The EU has initiated a process to create labeling regulations for unintentional contagion but it is non expected to be published before 2024.[83]

Lack of compliance with labeling regulations is also a problem. As an example, the FDA documented failure to list milk every bit an ingredient in dark chocolate bars. The FDA tested 94 dark chocolate bars for the presence of milk. Only six listed milk as an ingredient, but of the remaining 88, the FDA constitute that 51 of them actually did contain milk proteins. Many of those did have PAL wording such equally "may comprise dairy." Others claimed to be "dairy costless" or "vegan" just even so tested positive for cow's milk proteins.[84]

In Brazil, since April 2016, the declaration of the possibility of cross-contamination is mandatory when the product does not intentionally add together whatsoever allergenic nutrient or its derivatives, only the Skillful Manufacturing Practices and allergen control measures adopted are not sufficient to forestall the presence of accidental trace amounts. Milk of all species of mammalians is included amidst these allergenic foods.[12]

Research [edit]

Desensitization, which is a slow procedure of consuming tiny amounts of the allergenic protein until the body is able to tolerate more meaning exposure, results in reduced symptoms or fifty-fifty remission of the allergy in some people and is beingness explored for handling of milk allergy.[85] This is chosen oral immunotherapy (OIT). Sublingual immunotherapy, in which the allergenic protein is held in the rima oris nether the natural language, has been approved for grass and ragweed allergies, simply non yet for foods.[86] [87] Oral desensitization for moo-cow'southward milk allergy appears to be relatively safe and may exist effective, all the same further studies are required to understand the overall immune response, and questions remain open up about duration of the desensitization.[8] [sixteen] [17] [49]

At that place is research – not specific to milk allergy – on the utilise of probiotics, prebiotics and the combination of the two (synbiotics) equally a ways of treating or preventing infant and kid allergies. From reviews, in that location appears to be a treatment benefit for eczema,[88] [89] [90] simply not asthma, wheezing or rhinoconjunctivitis.[89] [91] Several reviews concluded that the prove is sufficient for it to exist recommended in clinical practise.[ninety] [92] [93]

Run across likewise [edit]

- Lactose intolerance

- List of allergens (food and not-food)

- Plant milk

References [edit]

- ^ a b Nwaru BI, Hickstein 50, Panesar SS, Roberts G, Muraro A, Sheikh A (August 2014). "Prevalence of mutual food allergies in Europe: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Allergy. 69 (8): 992–1007. doi:10.1111/all.12423. PMID 24816523. S2CID 28692645.

- ^ a b Caffarelli C, Baldi F, Bendandi B, Calzone Fifty, Marani 1000, Pasquinelli P (January 2010). "Moo-cow's milk protein allergy in children: a practical guide". Italian Journal of Pediatrics. 36: 5. doi:ten.1186/1824-7288-36-5. PMC2823764. PMID 20205781.

- ^ "Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America". Archived from the original on 6 October 2012. Retrieved 23 Dec 2012.

- ^ a b c d e FDA. "Food Allergen Labeling and Consumer Protection Act of 2004 Questions and Answers". Nutrient and Drug Administration . Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g FDA (18 December 2017). "Food Allergies: What You Demand to Know". Food and Drug Administration . Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- ^ a b Urisu A, Ebisawa Yard, Ito Thousand, Aihara Y, Ito South, Mayumi Grand, Kohno Y, Kondo North (September 2014). "Japanese Guideline for Food Allergy 2014". Allergology International. 63 (3): 399–419. doi:10.2332/allergolint.14-RAI-0770. PMID 25178179.

- ^ a b c "Food allergen labelling and information requirements nether the European union Food Information for Consumers Regulation No. 1169/2011: Technical Guidance" (Apr 2015).

- ^ a b c d eastward f k Lifschitz C, Szajewska H (February 2015). "Cow's milk allergy: evidence-based diagnosis and direction for the practitioner". European Journal of Pediatrics. 174 (2): 141–l. doi:ten.1007/s00431-014-2422-3. PMC4298661. PMID 25257836.

- ^ a b Taylor SL, Hefle SL (June 2006). "Food allergen labeling in the USA and Europe". Current Opinion in Allergy and Clinical Immunology (Review). six (three): 186–ninety. doi:x.1097/01.all.0000225158.75521.ad. PMID 16670512. S2CID 25204657.

- ^ Taylor SL, Hefle SL, Bindslev-Jensen C, Atkins FM, Andre C, Bruijnzeel-Koomen C, et al. (May 2004). "A consensus protocol for the determination of the threshold doses for allergenic foods: how much is as well much?". Clinical and Experimental Allergy (Review. Consensus Evolution Conference. Research Support, Non-U.Due south. Gov't). 34 (5): 689–95. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.1886.x. PMID 15144458. S2CID 3071478.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Allen KJ, Turner PJ, Pawankar R, Taylor S, Sicherer S, Lack G, Rosario N, Ebisawa Yard, Wong G, Mills EN, Beyer K, Fiocchi A, Sampson HA (2014). "Precautionary labelling of foods for allergen content: are nosotros gear up for a global framework?". The Earth Allergy Organisation Journal. 7 (1): one–14. doi:x.1186/1939-4551-7-x. PMC4005619. PMID 24791183.

- ^ a b c "Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária Guia sobre Programa de Controle de Alergênicos". Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (ANVISA). 2016. Archived from the original on 29 April 2018. Retrieved seven April 2018.

- ^ a b c Barbarous J, Johns CB (February 2015). "Food allergy: epidemiology and natural history". Immunology and Allergy Clinics of North America. 35 (1): 45–59. doi:10.1016/j.iac.2014.09.004. PMC4254585. PMID 25459576.

- ^ Vandenplas Y (July 2017). "Prevention and Management of Cow'due south Milk Allergy in Non-Exclusively Breastfed Infants". Nutrients. 9 (7): 731. doi:10.3390/nu9070731. PMC5537845. PMID 28698533.

- ^ a b Liu AH, Jaramillo R, Sicherer SH, Forest RA, Bock SA, Burks AW, Massing K, Cohn RD, Zeldin DC (October 2010). "National prevalence and gamble factors for food allergy and relationship to asthma: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005-2006". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 126 (four): 798–806.e13. doi:ten.1016/j.jaci.2010.07.026. PMC2990684. PMID 20920770.

- ^ a b Martorell Calatayud C, Muriel García A, Martorell Aragonés A, De La Hoz Caballer B (2014). "Prophylactic and efficacy profile and immunological changes associated with oral immunotherapy for IgE-mediated moo-cow'south milk allergy in children: systematic review and meta-analysis". Periodical of Investigational Allergology & Clinical Immunology. 24 (five): 298–307. PMID 25345300.

- ^ a b Brożek JL, Terracciano Fifty, Hsu J, Kreis J, Compalati E, Santesso Northward, et al. (March 2012). "Oral immunotherapy for IgE-mediated cow's milk allergy: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Clinical and Experimental Allergy. 42 (iii): 363–74. doi:ten.1111/j.1365-2222.2011.03948.x. PMID 22356141. S2CID 25333442.

- ^ a b Koletzko Due south, Niggemann B, Arato A, Dias JA, Heuschkel R, Husby Southward, et al. (August 2012). "Diagnostic approach and management of cow'due south-milk poly peptide allergy in infants and children: ESPGHAN GI Commission practical guidelines". Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition (Do Guideline). 55 (2): 221–9. doi:10.1097/MPG.0b013e31825c9482. PMID 22569527.

- ^ a b c MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Food allergy

- ^ a b Sicherer SH, Sampson HA (February 2014). "Nutrient allergy: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and handling". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 133 (two): 291–307, quiz 308. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2013.eleven.020. PMID 24388012.

- ^ Venter C, Chocolate-brown T, Meyer R, Walsh J, Shah Northward, Nowak-Węgrzyn A, et al. (2017). "Better recognition, diagnosis and management of not-IgE-mediated moo-cow's milk allergy in infancy: iMAP-an international interpretation of the MAP (Milk Allergy in Primary Care) guideline". Clinical and Translational Allergy. 7: 26. doi:10.1186/s13601-017-0162-y. PMC5567723. PMID 28852472.

- ^ a b Leonard SA (November 2017). "Not-IgE-mediated Adverse Food Reactions". Current Allergy and Asthma Reports. 17 (12): 84. doi:x.1007/s11882-017-0744-8. PMID 29138990. S2CID 207324496.

- ^ a b Caubet JC, Szajewska H, Shamir R, Nowak-Węgrzyn A (February 2017). "Non-IgE-mediated gastrointestinal food allergies in children". Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. 28 (i): 6–17. doi:ten.1111/pai.12659. PMID 27637372. S2CID 6619743.

- ^ a b Nowak-Węgrzyn A, Chehade Thou, Groetch ME, Spergel JM, Wood RA, Allen One thousand, et al. (Apr 2017). "International consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome: Executive summary-Workgroup Report of the Adverse Reactions to Foods Committee, American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 139 (four): 1111–1126.e4. doi:x.1016/j.jaci.2016.12.966. PMID 28167094.

- ^ "Food allergy". NHS Choices. 16 May 2016. Retrieved 31 January 2017.

A nutrient allergy is when the body'southward immune system reacts unusually to specific foods

- ^ Food Reactions. Allergies Archived 2010-04-16 at the Wayback Machine. Foodreactions.org. Kent, England. 2005. Accessed 27 Apr 2010.

- ^ Mayo Clinic. Causes of Nutrient Allergies. Archived 2010-02-27 at the Wayback Machine April 2010.

- ^ a b c Janeway C, Paul Travers, Mark Walport, Mark Shlomchik (2001). Immunobiology; Fifth Edition. New York and London: Garland Scientific discipline. pp. due east–book. ISBN978-0-8153-4101-vii. Archived from the original on 2009-06-28.

- ^ a b Grimbaldeston MA, Metz M, Yu Yard, Tsai M, Galli SJ (December 2006). "Effector and potential immunoregulatory roles of mast cells in IgE-associated caused immune responses". Current Opinion in Immunology. 18 (6): 751–lx. doi:10.1016/j.coi.2006.09.011. PMID 17011762.

- ^ Holt PG, Sly PD (Oct 2007). "Th2 cytokines in the asthma tardily-phase response". Lancet. 370 (9596): 1396–eight. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61587-6. PMID 17950849. S2CID 40819814.

- ^ Soares-Weiser K, Takwoingi Y, Panesar SS, Muraro A, Werfel T, Hoffmann-Sommergruber M, Roberts G, Halken South, Poulsen 50, van Ree R, Vlieg-Boerstra BJ, Sheikh A (January 2014). "The diagnosis of food allergy: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Allergy. 69 (i): 76–86. doi:10.1111/all.12333. PMID 24329961. S2CID 21493978.

- ^ Cuomo B, Indirli GC, Bianchi A, Arasi South, Caimmi D, Dondi A, La Grutta S, Panetta 5, Verga MC, Calvani One thousand (October 2017). "Specific IgE and skin prick tests to diagnose allergy to fresh and baked cow'due south milk according to age: a systematic review". Italian Journal of Pediatrics. 43 (i): 93. doi:10.1186/s13052-017-0410-viii. PMC5639767. PMID 29025431.

- ^ a b Heine RG, AlRefaee F, Bachina P, De Leon JC, Geng L, Gong Southward, Madrazo JA, Ngamphaiboon J, Ong C, Rogacion JM (2017). "Lactose intolerance and gastrointestinal cow's milk allergy in infants and children - common misconceptions revisited". The World Allergy Organization Journal. 10 (1): 41. doi:10.1186/s40413-017-0173-0. PMC5726035. PMID 29270244.

- ^ Feuille E, Nowak-Węgrzyn A (August 2015). "Food Protein-Induced Enterocolitis Syndrome, Allergic Proctocolitis, and Enteropathy". Current Allergy and Asthma Reports. 15 (8): fifty. doi:ten.1007/s11882-015-0546-9. PMID 26174434. S2CID 6651513.

- ^ Guandalini S, Newland C (Oct 2011). "Differentiating food allergies from food intolerances". Electric current Gastroenterology Reports (Review). xiii (5): 426–34. doi:10.1007/s11894-011-0215-seven. PMID 21792544. S2CID 207328783.

- ^ Deng Y, Misselwitz B, Dai N, Trick Thousand (September 2015). "Lactose Intolerance in Adults: Biological Mechanism and Dietary Management". Nutrients (Review). vii (9): 8020–35. doi:ten.3390/nu7095380. PMC4586575. PMID 26393648.

- ^ Heyman MB (September 2006). "Lactose intolerance in infants, children, and adolescents". Pediatrics. 118 (3): 1279–86. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-1721. PMID 16951027.

- ^ a b c d due east "Lactose Intolerance". NIDDK. June 2014. Archived from the original on 25 October 2016. Retrieved 25 October 2016.

- ^ Berni Canani R, Pezzella 5, Amoroso A, Cozzolino T, Di Scala C, Passariello A (March 2016). "Diagnosing and Treating Intolerance to Carbohydrates in Children". Nutrients. 8 (3): 157. doi:10.3390/nu8030157. PMC4808885. PMID 26978392.

- ^ de Silva D, Geromi Thousand, Halken S, Host A, Panesar SS, Muraro A, et al. (May 2014). "Chief prevention of food allergy in children and adults: systematic review". Allergy. 69 (5): 581–9. doi:x.1111/all.12334. PMID 24433563. S2CID 23987626.

- ^ a b c Kramer MS, Kakuma R (June 2014). "Maternal dietary antigen avoidance during pregnancy or lactation, or both, for preventing or treating atopic disease in the child". Evidence-Based Kid Health. 9 (ii): 447–83. doi:10.1002/ebch.1972. PMID 25404609.

- ^ a b National Academies of Sciences, Engineering science, and Medicine, Health and Medicine Division, Food and Nutrition Board, Commission on Food Allergies: Global Burden, Causes, Treatment, Prevention, and Public Policy (November 2016). Oria MP, Stallings VA (eds.). Finding a Path to Safety in Food Allergy: Assessment of the Global Burden, Causes, Prevention, Management, and Public Policy. ISBN978-0-309-45031-7. PMID 28609025. CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Anderson J, Malley K, Snell R (July 2009). "Is half-dozen months even so the best for exclusive breastfeeding and introduction of solids? A literature review with consideration to the risk of the development of allergies". Breastfeeding Review. 17 (ii): 23–31. PMID 19685855.

- ^ a b Fiocchi A, Dahda L, Dupont C, Campoy C, Fierro V, Nieto A (2016). "Cow'south milk allergy: towards an update of DRACMA guidelines". The World Allergy Organization Periodical. 9 (ane): 35. doi:ten.1186/s40413-016-0125-0. PMC5109783. PMID 27895813.

- ^ Labeling of Infant Formula: Guidance for Industry U.Due south. Food and Drug Assistants (2016) Accessed 11 December 2017.

- ^ Boyle RJ, Ierodiakonou D, Khan T, Chivinge J, Robinson Z, Geoghegan Northward, Jarrold Thousand, Afxentiou T, Reeves T, Cunha S, Trivella M, Garcia-Larsen V, Leonardi-Bee J (March 2016). "Hydrolysed formula and risk of allergic or autoimmune disease: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ. 352: i974. doi:10.1136/bmj.i974. PMC4783517. PMID 26956579.

- ^ a b c d Kattan JD, Cocco RR, Järvinen KM (Apr 2011). "Milk and soy allergy". Pediatric Clinics of N America (Review). 58 (two): 407–26, x. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2011.02.005. PMC3070118. PMID 21453810.

- ^ Luyt D, Ball H, Makwana N, Green MR, Bravin K, Nasser SM, Clark AT (2014). "BSACI guideline for the diagnosis and management of moo-cow's milk allergy". Clin. Exp. Allergy. 44 (five): 642–72. doi:10.1111/cea.12302. PMID 24588904. S2CID 204981786.

- ^ a b Yeung JP, Kloda LA, McDevitt J, Ben-Shoshan M, Alizadehfar R (November 2012). "Oral immunotherapy for milk allergy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 11: CD009542. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009542.pub2. PMC7390504. PMID 23152278.

- ^ Tang AW (Oct 2003). "A applied guide to anaphylaxis". American Family Physician. 68 (7): 1325–32. PMID 14567487.

- ^ The EAACI Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Guidelines Group, Muraro A, Roberts G, Worm Grand, Bilò MB, Brockow K, et al. (August 2014). "Anaphylaxis: guidelines from the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology". Allergy. 69 (viii): 1026–45. doi:10.1111/all.12437. PMID 24909803. S2CID 11054771.

- ^ Moneret-Vautrin DA, Kanny K (June 2004). "Update on threshold doses of food allergens: implications for patients and the nutrient industry". Current Opinion in Allergy and Clinical Immunology (Review). iv (3): 215–9. doi:10.1097/00130832-200406000-00014. PMID 15126945. S2CID 41402604.

- ^ a b Allen KJ, Remington BC, Baumert JL, Crevel RW, Houben GF, Brooke-Taylor S, Kruizinga AG, Taylor SL (January 2014). "Allergen reference doses for precautionary labeling (VITAL 2.0): clinical implications". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 133 (1): 156–64. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2013.06.042. PMID 23987796.

- ^ a b c d e f FDA (xiv December 2017). "Accept Food Allergies? Read the Characterization". Food and Drug Administration . Retrieved 14 Jan 2018.

- ^ a b c "Food Ingredients of Public Health Business organisation" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture. Food Condom and Inspection Service. 7 March 2017. Retrieved 16 February 2018.

- ^ a b c "Allergies and Nutrient Condom". United States Section of Agriculture. Nutrient Rubber and Inspection Service. 1 Dec 2016. Retrieved xvi February 2018.

- ^ a b "Milk Allergy Nutrition" (PDF). University of Wisconsin Infirmary and Clinics. Clinical Nutrition Services Department and the Department of Nursing. 2015. Retrieved 14 Jan 2018.

- ^ FDA (12 Oct 2014). "Finding Food Allergens Where They Shouldn't Be". Food and Drug Administration . Retrieved xi Feb 2018.

- ^ Martorell-Aragonés A, Echeverría-Zudaire L, Alonso-Lebrero Due east, Boné-Calvo J, Martín-Muñoz MF, Nevot-Falcó S, Piquer-Gibert 1000, Valdesoiro-Navarrete L (2015). "Position certificate: IgE-mediated moo-cow'south milk allergy". Allergologia et Immunopathologia (Practice Guideline. Review). 43 (5): 507–26. doi:10.1016/j.aller.2015.01.003. PMID 25800671.

- ^ Nanagas VC, Baldwin JL, Karamched KR (July 2017). "Hidden Causes of Anaphylaxis". Current Allergy and Asthma Reports. 17 (7): 44. doi:10.1007/s11882-017-0713-2. PMID 28577270. S2CID 33691910.

- ^ Martín-Muñoz MF, Fortuni Thousand, Caminoa M, Belver T, Quirce S, Caballero T (Dec 2012). "Anaphylactic reaction to probiotics. Moo-cow'south milk and hen's egg allergens in probiotic compounds". Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. 23 (eight): 778–84. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3038.2012.01338.10. PMID 22957765. S2CID 41223984.

- ^ "Milk Soy Protein Intolerance (MSPI)". dhhs.ne.gov. 2017. Archived from the original on fourteen Jan 2018. Retrieved xiv Feb 2018.

- ^ Bhatia J, Greer F (May 2008). "Employ of soy protein-based formulas in babe feeding". Pediatrics. 121 (5): 1062–eight. doi:x.1542/peds.2008-0564. PMID 18450914.

- ^ a b Skripak JM, Matsui EC, Mudd K, Wood RA (November 2007). "The natural history of IgE-mediated cow'due south milk allergy". The Periodical of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 120 (five): 1172–7. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2007.08.023. PMID 17935766.

- ^ Fiocchi A, Restani P, Riva E (June 2000). "Beef allergy in children". Nutrition. xvi (6): 454–7. doi:10.1016/s0899-9007(00)00285-9. PMID 10869903.

- ^ Robbins KA, Wood RA, Keet CA (December 2014). "Milk allergy is associated with decreased growth in US children". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 134 (6): 1466–1468.e6. doi:ten.1016/j.jaci.2014.08.037. PMC4362703. PMID 25312758.

- ^ "What is Prevalence?" National Establish of Mental Health (Accessed 25 December 2020).

- ^ Smith, Matthew (2015). Some other Person'southward Poison: A History of Food Allergy. New York City, New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 22–23, 26. ISBN978-0-231-53919-7.

- ^ Ravid NL, Annunziato RA, Ambrose MA, Chuang Grand, Mullarkey C, Sicherer SH, Shemesh E, Cox AL (March 2015). "Mental wellness and quality-of-life concerns related to the burden of food allergy". The Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 38 (1): 77–89. doi:x.1016/j.psc.2014.11.004. PMID 25725570.

- ^ Morou Z, Tatsioni A, Dimoliatis ID, Papadopoulos NG (2014). "Wellness-related quality of life in children with food allergy and their parents: a systematic review of the literature". Journal of Investigational Allergology & Clinical Immunology. 24 (6): 382–95. PMID 25668890.

- ^ a b Lange L (2014). "Quality of life in the setting of anaphylaxis and nutrient allergy". Allergo Journal International. 23 (7): 252–260. doi:10.1007/s40629-014-0029-10. PMC4479473. PMID 26120535.

- ^ a b van der Velde JL, Dubois AE, Flokstra-de Blok BM (Dec 2013). "Nutrient allergy and quality of life: what take we learned?". Electric current Allergy and Asthma Reports. 13 (6): 651–61. doi:ten.1007/s11882-013-0391-7. PMID 24122150. S2CID 326837.

- ^ Shah Eastward, Pongracic J (Baronial 2008). "Food-induced anaphylaxis: who, what, why, and where?". Pediatric Register. 37 (8): 536–41. doi:10.3928/00904481-20080801-06. PMID 18751571.

- ^ Fong AT, Katelaris CH, Wainstein B (July 2017). "Bullying and quality of life in children and adolescents with food allergy". Periodical of Paediatrics and Child Health. 53 (7): 630–635. doi:10.1111/jpc.13570. PMID 28608485. S2CID 9719096.

- ^ Shah AV, Serajuddin AT, Mangione RA (May 2018). "Making All Medications Gluten Free". Periodical of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 107 (five): 1263–1268. doi:10.1016/j.xphs.2017.12.021. PMID 29287928.

- ^ Roses JB (2011). "Food allergen law and the Food Allergen Labeling and Consumer Protection Act of 2004: falling short of true protection for food allergy sufferers". Nutrient and Drug Police Periodical. 66 (2): 225–42, ii. PMID 24505841.

- ^ Mills EN, Valovirta E, Madsen C, Taylor SL, Vieths S, Anklam E, Baumgartner S, Koch P, Crevel RW, Frewer L (December 2004). "Information provision for allergic consumers--where are we going with food allergen labelling?". Allergy. 59 (12): 1262–viii. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2004.00720.x. PMID 15507093. S2CID 40395908.

- ^ Taylor SL, Baumert JL (2015). "Worldwide nutrient allergy labeling and detection of allergens in processed foods". Food Allergy: Molecular Footing and Clinical Practise. Chemical Immunology and Allergy. Vol. 101. pp. 227–34. doi:10.1159/000373910. ISBN978-iii-318-02340-4. PMID 26022883.

- ^ a b DunnGalvin A, Chan CH, Crevel R, Grimshaw K, Poms R, Schnadt S, et al. (September 2015). "Precautionary allergen labelling: perspectives from central stakeholder groups". Allergy. 70 (nine): 1039–51. doi:x.1111/all.12614. PMID 25808296. S2CID 18362869.

- ^ Zurzolo GA, de Courten 1000, Koplin J, Mathai ML, Allen KJ (June 2016). "Is advising nutrient allergic patients to avoid food with precautionary allergen labelling out of engagement?". Electric current Stance in Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 16 (3): 272–seven. doi:10.1097/ACI.0000000000000262. PMID 26981748. S2CID 21326926.

- ^ Taylor SL, Baumert JL, Kruizinga AG, Remington BC, Crevel RW, Brooke-Taylor Due south, Allen KJ, Houben Thou (January 2014). "Establishment of Reference Doses for residues of allergenic foods: report of the VITAL Practiced Panel". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 63: 9–17. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2013.10.032. PMID 24184597.

- ^ The VITAL Program Allergen Agency, Australia and New Zealand.

- ^ Popping B, Diaz-Amigo C (January 2018). "European Regulations for Labeling Requirements for Food Allergens and Substances Causing Intolerances: History and Time to come". Periodical of AOAC International. 101 (1): 2–7. doi:x.5740/jaoacint.17-0381. PMID 29202901.

- ^ "Consumer Updates – Dark Chocolate and Milk Allergies". FDA. 2017. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ^ Nowak-Węgrzyn A, Sampson HA (March 2011). "Futurity therapies for food allergies". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 127 (3): 558–73, quiz 574–5. doi:x.1016/j.jaci.2010.12.1098. PMC3066474. PMID 21277625.

- ^ Narisety SD, Keet CA (October 2012). "Sublingual vs oral immunotherapy for nutrient allergy: identifying the right approach". Drugs. 72 (fifteen): 1977–89. doi:ten.2165/11640800-000000000-00000. PMC3708591. PMID 23009174.

- ^ http://acaai.org/allergies/allergy-treatment/allergy-immunotherapy/sublingual-immunotherapy-slit/ Sublingual Therapy (SLIT) American Higher of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology

- ^ Chang YS, Trivedi MK, Jha A, Lin YF, Dimaano L, García-Romero MT (March 2016). "Synbiotics for Prevention and Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials". JAMA Pediatrics. 170 (iii): 236–42. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.3943. PMID 26810481.

- ^ a b Cuello-Garcia CA, Brożek JL, Fiocchi A, Pawankar R, Yepes-Nuñez JJ, Terracciano L, Gandhi S, Agarwal A, Zhang Y, Schünemann HJ (October 2015). "Probiotics for the prevention of allergy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 136 (iv): 952–61. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2015.04.031. PMID 26044853.

- ^ a b Osborn DA, Sinn JK (March 2013). "Prebiotics in infants for prevention of allergy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD006474. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006474.pub3. PMID 23543544.

- ^ Zuccotti 1000, Meneghin F, Aceti A, Barone G, Callegari ML, Di Mauro A, Fantini MP, Gori D, Indrio F, Maggio L, Morelli L, Corvaglia L (November 2015). "Probiotics for prevention of atopic diseases in infants: systematic review and meta-analysis". Allergy. seventy (11): 1356–71. doi:10.1111/all.12700. PMID 26198702.

- ^ de Silva D, Geromi Grand, Panesar SS, Muraro A, Werfel T, Hoffmann-Sommergruber M, et al. (February 2014). "Acute and long-term management of food allergy: systematic review". Allergy. 69 (2): 159–67. doi:10.1111/all.12314. PMID 24215577. S2CID 206999857.

- ^ Zhang GQ, Hu HJ, Liu CY, Zhang Q, Shakya S, Li ZY (February 2016). "Probiotics for Prevention of Atopy and Food Hypersensitivity in Early Childhood: A PRISMA-Compliant Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials". Medicine. 95 (8): e2562. doi:x.1097/Doc.0000000000002562. PMC4778993. PMID 26937896.

External links [edit]

- Milk Allergy at Food Allergy Initiative

petersonhoust1940.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Milk_allergy

Post a Comment for "what are the components of milk that people are allergic to"